Recently, we were required to implement a custom “New Project Wizard” for use in a client’s internal QGIS installation. The goal here was that users would be required to fill out certain metadata fields whenever they created a new QGIS project.

Fortunately, the PyQGIS (and underlying Qt) libraries makes this possibly, and relatively straightforward to do. Qt has a powerful API for creating multi-page “wizard” type dialogs, via the QWizard and QWizardPage classes. Let’s have a quick look at writing a custom wizard using these classes, and finally we’ll hook it into the QGIS interface using some PyQGIS magic.

We’ll start super simple, creating a single page wizard with no settings. To do this we first create a Page1 subclass of QWizardPage, a ProjectWizard subclass of QWizard, and a simple runNewProjectWizard function which launches the wizard. (The code below is designed for QGIS 3.0, but will run with only small modifications on QGIS 2.x):

class Page1(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.setTitle('General Properties')

self.setSubTitle('Enter general properties for this project.')

class ProjectWizard(QWizard):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.addPage(Page1(self))

self.setWindowTitle("New Project")

def runNewProjectWizard():

d=ProjectWizard()

d.exec()

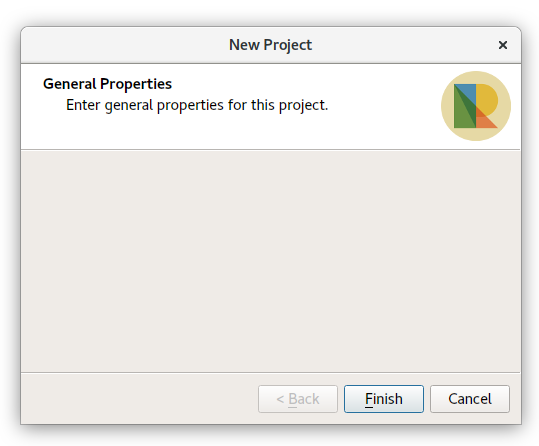

If this code is executed in the QGIS Python console, you’ll see something like this:

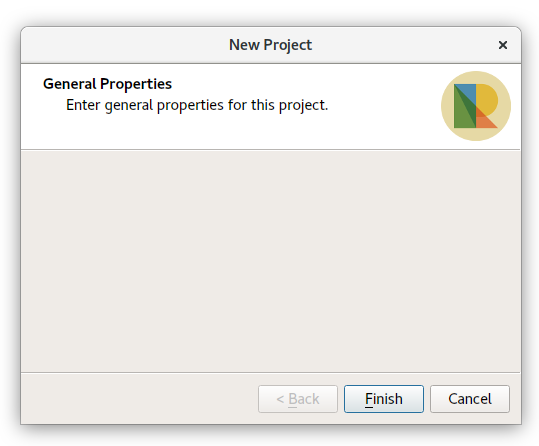

Not too fancy (or functional) yet, but still not bad for 20 lines of code! We can instantly make this a bit nicer by inserting a custom logo into the widget. This is done by calling setPixmap inside the ProjectWizard constructor.

class ProjectWizard(QWizard):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.addPage(Page1(self))

self.setWindowTitle("New Project")

logo_image = QImage('path_to_logo.png')

self.setPixmap(QWizard.LogoPixmap, QPixmap.fromImage(logo_image))

That’s a bit nicer. QWizard has HEAPS of options for tweaking the wizards — best to read about those over at the Qt documentation. Our next step is to start adding some settings to this wizard. We’ll keep things easy for now and just insert a number of text input boxes (QLineEdits) into Page1:

class Page1(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.setTitle('General Properties')

self.setSubTitle('Enter general properties for this project.')

# create some widgets

self.project_number_line_edit = QLineEdit()

self.project_title_line_edit = QLineEdit()

self.author_line_edit = QLineEdit()

# set the page layout

layout = QGridLayout()

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Project Number'),0,0)

layout.addWidget(self.project_number_line_edit,0,1)

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Title'),1,0)

layout.addWidget(self.project_title_line_edit,1,1)

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Author'),2,0)

layout.addWidget(self.author_line_edit,2,1)

self.setLayout(layout)

There’s nothing particularly new here, especially if you’ve used Qt widgets before. We make a number of QLineEdit widgets, and then create a grid layout containing these widgets and accompanying labels (QLabels). Here’s the result if we run our wizard now:

So now there’s the option to enter a project number, title and author. The next step is to force users to populate these fields before they can complete the wizard. Fortunately, QWizardPage has us covered here and we can use the registerField() function to do this. By calling registerField, we make the wizard aware of the settings we’ve added on this page, allowing us to retrieve their values when the wizard completes. We can also use registerField to automatically force their population by appending a * to the end of the field names. Just like this…

class Page1(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

...

self.registerField('number*',self.project_number_line_edit)

self.registerField('title*',self.project_title_line_edit)

self.registerField('author*',self.author_line_edit)

If we ran the wizard now, we’d be forced to enter something for project number, title and author before the Finish button becomes enabled. Neat! By registering the fields, we’ve also allowed their values to be retrieved after the wizard completes. Let’s alter runNewProjectWizard to retrieve these values and do something with them:

def runNewProjectWizard():

d=ProjectWizard()

d.exec()

# Set the project title

title=d.field('title')

QgsProject.instance().setTitle(d.field('title'))

# Create expression variables for the author and project number

number=d.field('number')

QgsExpressionContextUtils.setProjectVariable(QgsProject.instance(),'project_number', number)

author=d.field('author')

QgsExpressionContextUtils.setProjectVariable(QgsProject.instance(),'project_author', author)

Here, we set the project title directly and create expression variables for the project number and author. This allows their use within QGIS expressions via the @project_number and @project_author variables. Accordingly, they can be embedded into print layout templates so that layout elements are automatically populated with the corresponding author and project number. Nifty!

Ok, let’s beef up our wizard by adding a second page, asking the user to select a sensible projection (coordinate reference system) for their project. Thanks to improvements in QGIS 3.0, it’s super-easy to embed a powerful pre-made projection selector widget into your scripts, which even includes a handy preview of the area of the world that the projection is valid for.

class Page2(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.setTitle('Project Coordinate System')

self.setSubTitle('Choosing an appropriate projection is important to ensure accurate distance and area measurements.')

self.proj_selector = QgsProjectionSelectionTreeWidget()

layout = QVBoxLayout()

layout.addWidget(self.proj_selector)

self.setLayout(layout)

self.registerField('crs',self.proj_selector)

self.proj_selector.crsSelected.connect(self.crs_selected)

def crs_selected(self):

self.setField('crs',self.proj_selector.crs())

self.completeChanged.emit()

def isComplete(self):

return self.proj_selector.crs().isValid()

There’s a lot happening here. First, we subclass QWizardPage to create a second page in our widget. Then, just like before, we add some widgets to this page and set the page’s layout. In this case we are using the standard QgsProjectionSelectionTreeWidget to give users a projection choice. Again, we let the wizard know about our new setting by a call to registerField. However, since QWizard has no knowledge about how to handle a QgsProjectionSelectionTreeWidget, there’s a bit more to do here. So we make a connection to the projection selector’s crsSelected signal, hooking it up to a function which sets the wizard’s “crs” field value to the widget’s selected CRS. Here, we also emit the completeChanged signal, which indicates that the wizard page should re-validate the current settings. Lastly, we override QWizardPage’s isComplete method, checking that there’s a valid CRS selection in the selector widget. If we run the wizard now we’ll be forced to choose a valid CRS from the widget before the wizard allows us to proceed:

Lastly, we need to adapt runNewProjectWizard to also handle the projection setting:

def runNewProjectWizard():

d=ProjectWizard()

d.exec()

# Set the project crs

crs=d.field('crs')

QgsProject.instance().setCrs(crs)

# Set the project title

title=d.field('title')

...

Great! A fully functional New Project wizard. The final piece of the puzzle is triggering this wizard when a user creates a new project within QGIS. To do this, we hook into the iface.newProjectCreated signal. By connecting to this signal, our code will be called whenever the user creates a new project (after all the logic for saving and closing the current project has been performed). It’s as simple as this:

iface.newProjectCreated.connect(runNewProjectWizard)

Now, whenever a new project is made, our wizard is triggered – forcing users to populate the required fields and setting up the project accordingly!

There’s one last little bit to do – we also need to prevent users cancelling or closing the wizard before completing it. That’s done by changing a couple of settings in the ProjectWizard constructor, and by overriding the default reject method (which prevents closing the dialog by pressing escape).

class ProjectWizard(QWizard):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

...

self.setOption(QWizard.NoCancelButton, True)

self.setWindowFlags(self.windowFlags() | QtCore.Qt.CustomizeWindowHint)

self.setWindowFlags(self.windowFlags() & ~QtCore.Qt.WindowCloseButtonHint)

def reject(self):

pass

Here’s the full version of our code, ready for copying and pasting into the QGIS Python console:

icon_path = '/home/nyall/nr_logo.png'

class ProjectWizard(QWizard):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.addPage(Page1(self))

self.addPage(Page2(self))

self.setWindowTitle("New Project")

logo_image=QImage('path_to_logo.png')

self.setPixmap(QWizard.LogoPixmap, QPixmap.fromImage(logo_image))

self.setOption(QWizard.NoCancelButton, True)

self.setWindowFlags(self.windowFlags() | QtCore.Qt.CustomizeWindowHint)

self.setWindowFlags(self.windowFlags() & ~QtCore.Qt.WindowCloseButtonHint)

def reject(self):

pass

class Page1(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.setTitle('General Properties')

self.setSubTitle('Enter general properties for this project.')

# create some widgets

self.project_number_line_edit = QLineEdit()

self.project_title_line_edit = QLineEdit()

self.author_line_edit = QLineEdit()

# set the page layout

layout = QGridLayout()

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Project Number'),0,0)

layout.addWidget(self.project_number_line_edit,0,1)

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Title'),1,0)

layout.addWidget(self.project_title_line_edit,1,1)

layout.addWidget(QLabel('Author'),2,0)

layout.addWidget(self.author_line_edit,2,1)

self.setLayout(layout)

self.registerField('number*',self.project_number_line_edit)

self.registerField('title*',self.project_title_line_edit)

self.registerField('author*',self.author_line_edit)

class Page2(QWizardPage):

def __init__(self, parent=None):

super().__init__(parent)

self.setTitle('Project Coordinate System')

self.setSubTitle('Choosing an appropriate projection is important to ensure accurate distance and area measurements.')

self.proj_selector = QgsProjectionSelectionTreeWidget()

layout = QVBoxLayout()

layout.addWidget(self.proj_selector)

self.setLayout(layout)

self.registerField('crs',self.proj_selector)

self.proj_selector.crsSelected.connect(self.crs_selected)

def crs_selected(self):

self.setField('crs',self.proj_selector.crs())

self.completeChanged.emit()

def isComplete(self):

return self.proj_selector.crs().isValid()

def runNewProjectWizard():

d=ProjectWizard()

d.exec()

# Set the project crs

crs=d.field('crs')

QgsProject.instance().setCrs(crs)

# Set the project title

title=d.field('title')

QgsProject.instance().setTitle(d.field('title'))

# Create expression variables for the author and project number

number=d.field('number')

QgsExpressionContextUtils.setProjectVariable(QgsProject.instance(),'project_number', number)

author=d.field('author')

QgsExpressionContextUtils.setProjectVariable(QgsProject.instance(),'project_author', author)

iface.newProjectCreated.connect(runNewProjectWizard)

After a bit more than four months of development the new update release GRASS GIS 7.4.2 is available. It provides more than 50 stability fixes and improvements compared to the previous stable version 7.4.1. An overview of the new features in the 7.4 release series is available at

After a bit more than four months of development the new update release GRASS GIS 7.4.2 is available. It provides more than 50 stability fixes and improvements compared to the previous stable version 7.4.1. An overview of the new features in the 7.4 release series is available at