How to contribute to GRASS GIS development

How to contribute to GRASS GIS development: Guidance for new developers in the GRASS GIS Project.

The post How to contribute to GRASS GIS development appeared first on Markus Neteler Consulting.

How to contribute to GRASS GIS development: Guidance for new developers in the GRASS GIS Project.

The post How to contribute to GRASS GIS development appeared first on Markus Neteler Consulting.

This release is the first to support GeoPandas 1.0.

Additionally, this release adds multiple new features, including:

For the full change log, check out the release page.

We have also revamped the documentation at https://movingpandas.readthedocs.io/ using the PyData Sphinx Theme:

On a related note: if you know what I need to change to get all Trajectory functions listed in the TOC on the right, please let me know.

Last week, I had the pleasure to meet some of the people behind the OGC Moving Features Standard Working group at the IEEE Mobile Data Management Conference (MDM2024). While chatting about the Moving Features (MF) support in MovingPandas, I realized that, after the MF-JSON update & tutorial with official sample post, we never published a complete tutorial on working with MF-JSON encoded data in MovingPandas.

The current MovingPandas development version (to be release as version 0.19) supports:

This means that we can now go full circle: reading — writing — reading.

Both MF-JSON MovingPoint encoding and Trajectory encoding can be read using the MovingPandas function read_mf_json(). The complete Jupyter notebook for this tutorial is available in the project repo.

Here we read one of the official MF-JSON MovingPoint sample files:

traj = mpd.read_mf_json('data/movingfeatures.json')

To write MF-JSON, the Trajectory and TrajectoryCollection classes provide a to_mf_json() function:

The resulting Python dictionary in MF-JSON MovingPoint encoding can then be saved to a JSON file, and then read again:

import json

with open('mf1.json', 'w') as json_file:

json.dump(mf_json, json_file, indent=4)

Similarly, we can read any arbitrary trajectory data set and save it to MF-JSON.

For example, here we use our usual Geolife sample:

gdf = gp.read_file('data/demodata_geolife.gpkg')

tc = mpd.TrajectoryCollection(gdf, 'trajectory_id', t='t')

mf_json = tc.to_mf_json(temporal_columns=['sequence'])

import json

with open('mf5.json', 'w') as json_file:

json.dump(mf_json, json_file, indent=4)

tc = mpd.read_mf_json('mf5.json', traj_id_property='trajectory_id' )

The implemented MF-JSON support covers the basic usage of the encodings. There are some fine details in the standard, such as the distinction of time-varying attribute with linear versus step-wise interpolation, which MovingPandas currently does not support.

If you are working with movement data, I would appreciate if you can give the improved MF-JSON support a spin and report back with your experiences.

With the release of GeoPandas 1.0 this month, we’ve been finally able to close a long-standing issue in MovingPandas by adding support for the explore function which provides interactive maps using Folium and Leaflet.

Explore() will be available in the upcoming MovingPandas 0.19 release if your Python environment includes GeoPandas >= 1.0 and Folium. Of course, if you are curious, you can already test this new functionality using the current development version.

This enables users to access interactive trajectory plots even in environments where it is not possible to install geoviews / hvplot (the previously only option for interactive plots in MovingPandas).

I really like the legend for the speed color gradient, but unfortunately, the legend labels are not readable on the dark background map since they lack the semi-transparent white background that has been applied to the scale bar and credits label.

Speaking of reading / interpreting the plots …

You’ve probably seen the claims that AI will help make tools more accessible. Clearly AI can interpret and describe photos, but can it also interpret MovingPandas plots?

Not bad.

And what happens if we ask it to interpret the animated GIF from the beginning of the blog post?

So it looks like ChatGPT extracts 12 frames and analyzes them to answer our question:

Its guesses are not completely off but it made up the facts such as that the view shows “how traffic speeds vary over time”.

The problem remains that models such as ChatGPT rather make up interpretations than concede when they do not have enough information to make a reliable statement.

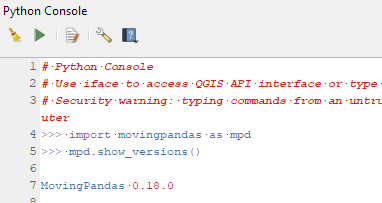

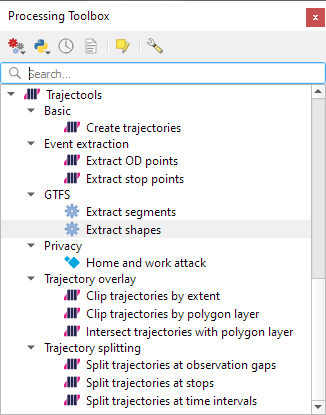

Today marks the 2.1 release of Trajectools for QGIS. This release adds multiple new algorithms and improvements. Since some improvements involve upstream MovingPandas functionality, I recommend to also update MovingPandas while you’re at it.

If you have installed QGIS and MovingPandas via conda / mamba, you can simply:

conda activate qgis

mamba install movingpandas=0.18Afterwards, you can check that the library was correctly installed using:

import movingpandas as mpd

mpd.show_versions()

The new Trajectools algorithms are:

Furthermore, we have fixed issue with previously ignored minimum trajectory length settings.

Scikit-mobility and gtfs_functions are optional dependencies. You do not need to install them, if you do not want to use the corresponding algorithms. In any case, they can be installed using mamba and pip:

mamba install scikit-mobility

pip install gtfs_functions

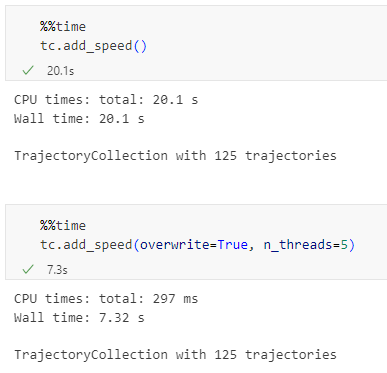

This release adds multiple new features, including

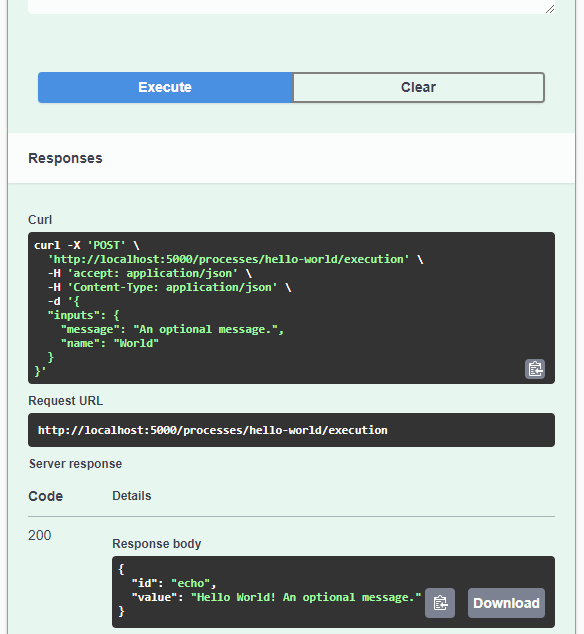

Today’s post is a quick introduction to pygeoapi, a Python server implementation of the OGC API suite of standards. OGC API provides many different standards but I’m particularly interested in OGC API – Processes which standardizes geospatial data processing functionality. pygeoapi implements this standard by providing a plugin architecture, thereby allowing developers to implement custom processing workflows in Python.

I’ll provide instructions for setting up and running pygeoapi on Windows using Powershell. The official docs show how to do this on Linux systems. The pygeoapi homepage prominently features instructions for installing the dev version. For first experiments, however, I’d recommend using a release version instead. So that’s what we’ll do here.

As a first step, lets install the latest release (0.16.1 at the time of writing) from conda-forge:

conda create -n pygeoapi python=3.10

conda activate pygeoapi

mamba install -c conda-forge pygeoapiNext, we’ll clone the GitHub repo to get the example config and datasets:

cd C:\Users\anita\Documents\GitHub\

git clone https://github.com/geopython/pygeoapi.git

cd pygeoapi\To finish the setup, we need some configurations:

cp pygeoapi-config.yml example-config.yml

# There is a known issue in pygeoapi 0.16.1: https://github.com/geopython/pygeoapi/issues/1597

# To fix it, edit the example-config.yml: uncomment the TinyDB option in the server settings (lines 51-54)

$Env:PYGEOAPI_CONFIG = "F:/Documents/GitHub/pygeoapi/example-config.yml"

$Env:PYGEOAPI_OPENAPI = "F:/Documents/GitHub/pygeoapi/example-openapi.yml"

pygeoapi openapi generate $Env:PYGEOAPI_CONFIG --output-file $Env:PYGEOAPI_OPENAPINow we can start the server:

pygeoapi serveAnd once the server is running, we can send requests, e.g. the list of processes:

curl.exe http://localhost:5000/processesAnd, of course, execute the example “hello-world” process:

curl.exe --% -X POST http://localhost:5000/processes/hello-world/execution -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d "{\"inputs\":{\"name\": \"hi there\"}}"As you can see, writing JSON content for curl is a pain. Luckily, pyopenapi comes with a nice web GUI, including Swagger UI for playing with all the functionality, including the hello-world process:

It’s not really a geospatial hello-world example, but it’s a first step.

Finally, I wan’t to leave you with a teaser since there are more interesting things going on in this space, including work on OGC API – Moving Features as shared by the pygeoapi team recently:

So, stay tuned.

Today, I want to point out a blog post over at

https://geocompx.org/post/2023/geocompy-bp1/

In this post, Jakub Nowosad introduces our book “Geocomputation with Python”, also known as geocompy. It is an open-source book on geographic data analysis with Python, written by Michael Dorman, Jakub Nowosad, Robin Lovelace, and me with contributions from others. You can find it online at https://py.geocompx.org/

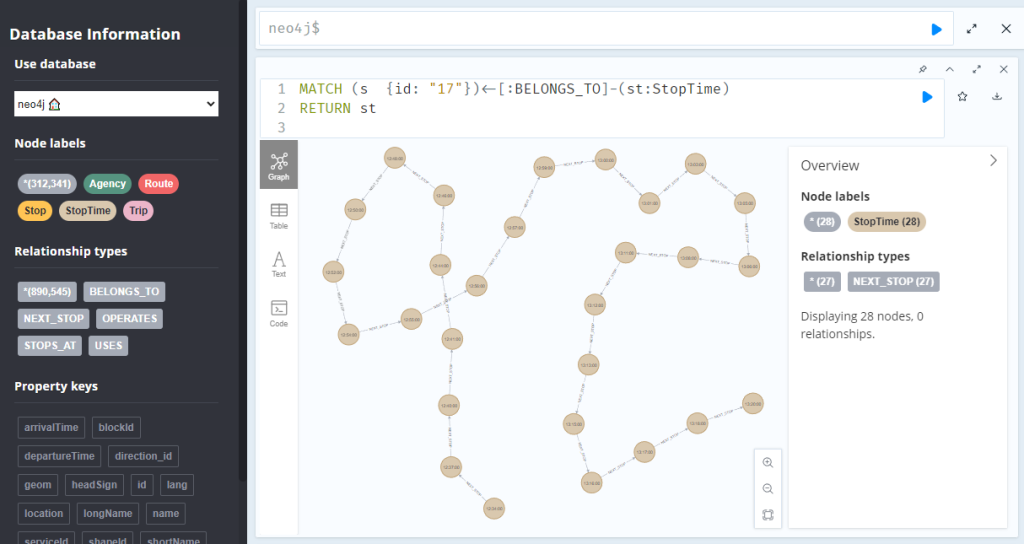

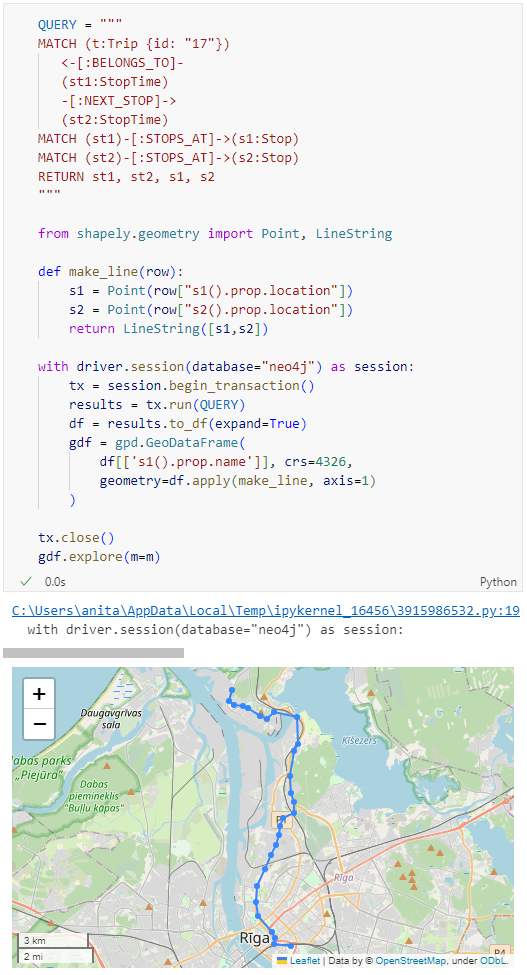

Previously, we mapped neo4j spatial nodes. This time, we want to take it one step further and map relationships.

A prime example, are the relationships between GTFS StopTime and Trip nodes. For example, this is the Cypher query to get all StopTime nodes of Trip 17:

MATCH

(t:Trip {id: "17"})

<-[:BELONGS_TO]-

(st:StopTime)

RETURN st

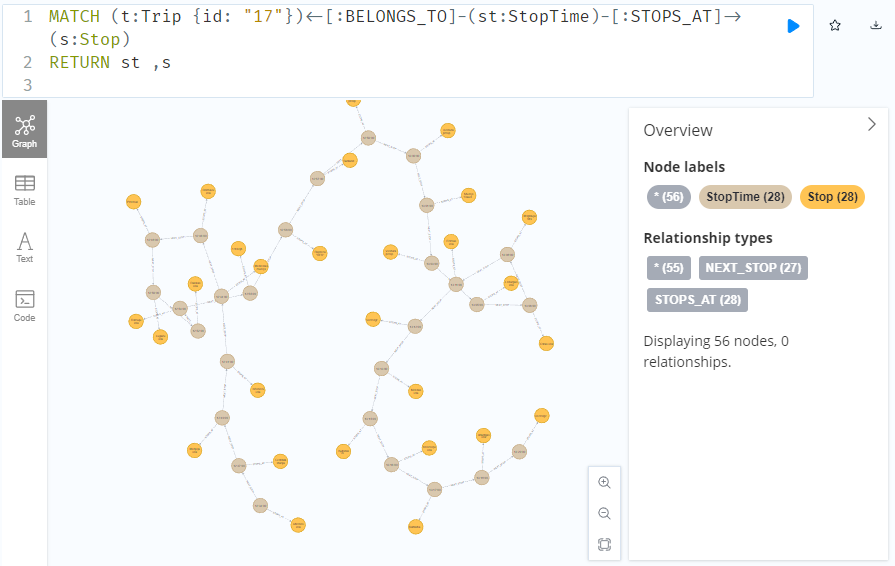

To get the stop locations, we also need to get the stop nodes:

MATCH

(t:Trip {id: "17"})

<-[:BELONGS_TO]-

(st:StopTime)

-[:STOPS_AT]->

(s:Stop)

RETURN st ,s

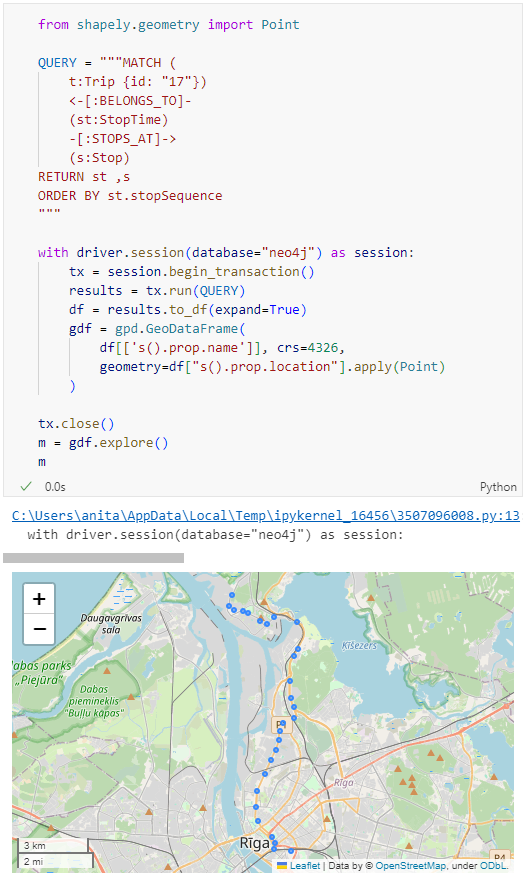

Adapting our code from the previous post, we can plot the stops:

from shapely.geometry import Point

QUERY = """MATCH (

t:Trip {id: "17"})

<-[:BELONGS_TO]-

(st:StopTime)

-[:STOPS_AT]->

(s:Stop)

RETURN st ,s

ORDER BY st.stopSequence

"""

with driver.session(database="neo4j") as session:

tx = session.begin_transaction()

results = tx.run(QUERY)

df = results.to_df(expand=True)

gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

df[['s().prop.name']], crs=4326,

geometry=df["s().prop.location"].apply(Point)

)

tx.close()

m = gdf.explore()

m

Ordering by stop sequence is actually completely optional. Technically, we could use the sorted GeoDataFrame, and aggregate all the points into a linestring to plot the route. But I want to try something different: we’ll use the NEXT_STOP relationships to get a DataFrame of the start and end stops for each segment:

QUERY = """

MATCH (t:Trip {id: "17"})

<-[:BELONGS_TO]-

(st1:StopTime)

-[:NEXT_STOP]->

(st2:StopTime)

MATCH (st1)-[:STOPS_AT]->(s1:Stop)

MATCH (st2)-[:STOPS_AT]->(s2:Stop)

RETURN st1, st2, s1, s2

"""

from shapely.geometry import Point, LineString

def make_line(row):

s1 = Point(row["s1().prop.location"])

s2 = Point(row["s2().prop.location"])

return LineString([s1,s2])

with driver.session(database="neo4j") as session:

tx = session.begin_transaction()

results = tx.run(QUERY)

df = results.to_df(expand=True)

gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(

df[['s1().prop.name']], crs=4326,

geometry=df.apply(make_line, axis=1)

)

tx.close()

gdf.explore(m=m)

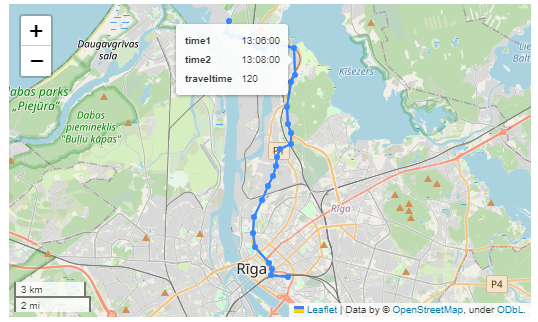

Finally, we can also use Cypher to calculate the travel time between two stops:

MATCH (t:Trip {id: "17"})

<-[:BELONGS_TO]-

(st1:StopTime)

-[:NEXT_STOP]->

(st2:StopTime)

MATCH (st1)-[:STOPS_AT]->(s1:Stop)

MATCH (st2)-[:STOPS_AT]->(s2:Stop)

RETURN st1.departureTime AS time1,

st2.arrivalTime AS time2,

s1.location AS geom1,

s2.location AS geom2,

duration.inSeconds(

time(st1.departureTime),

time(st2.arrivalTime)

).seconds AS traveltime

As always, here’s the notebook: https://github.com/anitagraser/QGIS-resources/blob/master/qgis3/notebooks/neo4j.ipynb

In the previous post, we investigated how to bring QGIS maps into Jupyter notebooks.

Today, we’ll take the next step and add basemaps to our maps. This is trickier than I would have expected. In particular, I was fighting with “invalid” OSM tile layers until I realized that my QGIS application instance somehow lacked the “WMS” provider.

In addition, getting basemaps to work also means that we have to take care of layer and project CRSes and on-the-fly reprojections. So let’s get to work:

from IPython.display import Image

from PyQt5.QtGui import QColor

from PyQt5.QtWidgets import QApplication

from qgis.core import QgsApplication, QgsVectorLayer, QgsProject, QgsRasterLayer, \

QgsCoordinateReferenceSystem, QgsProviderRegistry, QgsSimpleMarkerSymbolLayerBase

from qgis.gui import QgsMapCanvas

app = QApplication([])

qgs = QgsApplication([], False)

qgs.setPrefixPath(r"C:\temp", True) # setting a prefix path should enable the WMS provider

qgs.initQgis()

canvas = QgsMapCanvas()

project = QgsProject.instance()

map_crs = QgsCoordinateReferenceSystem('EPSG:3857')

canvas.setDestinationCrs(map_crs)

print("providers: ", QgsProviderRegistry.instance().providerList())

To add an OSM basemap, we use the xyz tiles option of the WMS provider:

urlWithParams = 'type=xyz&url=https://tile.openstreetmap.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png&zmax=19&zmin=0&crs=EPSG3857'

rlayer = QgsRasterLayer(urlWithParams, 'OpenStreetMap', 'wms')

print(rlayer.crs())

if rlayer.isValid():

project.addMapLayer(rlayer)

else:

print('invalid layer')

print(rlayer.error().summary())

If there are issues with the WMS provider, rlayer.error().summary() should point them out.

With both the vector layer and the basemap ready, we can finally plot the map:

canvas.setExtent(rlayer.extent())

plot_layers([vlayer,rlayer])

Of course, we can get more creative and style our vector layers:

vlayer.renderer().symbol().setColor(QColor("yellow"))

vlayer.renderer().symbol().symbolLayer(0).setShape(QgsSimpleMarkerSymbolLayerBase.Star)

vlayer.renderer().symbol().symbolLayer(0).setSize(10)

plot_layers([vlayer,rlayer])

And to switch to other basemaps, we just need to update the URL accordingly, for example, to load Carto tiles instead:

urlWithParams = 'type=xyz&url=http://basemaps.cartocdn.com/dark_all/{z}/{x}/{y}.png&zmax=19&zmin=0&crs=EPSG3857'

rlayer2 = QgsRasterLayer(urlWithParams, 'Carto', 'wms')

print(rlayer2.crs())

if rlayer2.isValid():

project.addMapLayer(rlayer2)

else:

print('invalid layer')

print(rlayer2.error().summary())

plot_layers([vlayer,rlayer2])

You can find the whole notebook at: https://github.com/anitagraser/QGIS-resources/blob/master/qgis3/notebooks/basemaps.ipynb

This summer, I had the honor to — once again — speak at the OpenGeoHub Summer School. This time, I wanted to challenge the students and myself by not just doing MovingPandas but by introducing both MovingPandas and DVC for Mobility Data Science.

I’ve previously written about DVC and how it may be used to track geoprocessing workflows with QGIS & DVC. In my summer school session, we go into details on how to use DVC to keep track of MovingPandas movement data analytics workflow.

Here is the recording of the session live stream and you can find the materials at https://github.com/movingpandas/movingpandas-examples/blob/opengeohub2023/README.md

This post is part of a series. Read more about movement data in GIS.

Today, I want to point out a blog post over at

https://geocompx.org/post/2023/ogh23/

written together with my fellow “Geocomputation with Python” co-authors Robin Lovelace, Michael Dorman, and Jakub Nowosad.

In this blog post, we talk about our experience teaching R and Python for geocomputation. The context of this blog post is the OpenGeoHub Summer School 2023 which has courses on R, Python and Julia. The focus of the blog post is on geographic vector data, meaning points, lines, polygons (and their ‘multi’ variants) and the attributes associated with them. We plan to cover raster data in a future post.

Das QGIS swiss locator Plugin erleichtert in der Schweiz vielen Anwendern das Leben dadurch, dass es die umfangreichen Geodaten von swisstopo und opendata.swiss zugänglich macht. Darunter ein breites Angebot an GIS Layern, aber auch Objektinformationen und eine Ortsnamensuche.

Dank eines Förderprojektes der Anwendergruppe Schweiz durfte OPENGIS.ch ihr Plugin um eine zusätzliche Funktionalität erweitern. Dieses Mal mit der Integration von WMTS als Datenquelle, eine ziemlich coole Sache. Doch was ist eigentlich der Unterschied zwischen WMS und WMTS?

Zuerst zu den Gemeinsamkeiten: Beide Protokolle – WMS und WMTS – sind dazu geeignet, Kartenbilder von einem Server zu einem Client zu übertragen. Dabei werden Rasterdaten, also Pixel, übertragen. Ausserdem werden dabei gerenderte Bilder übertragen, also keine Rohdaten. Diese sind dadurch für die Präsentation geeignet, im Browser, im Desktop GIS oder für einen PDF Export.

Der Unterschied liegt im T. Das T steht für “Tiled”, oder auf Deutsch “gekachelt”. Bei einem WMS (ohne Kachelung) können beliebige Bildausschnitte angefragt werden. Bei einem WMTS werden die Daten in einem genau vordefinierten Gitternetz — als Kacheln — ausgeliefert.

Der Hauptvorteil von WMTS liegt in dieser Standardisierung auf einem Gitternetz. Dadurch können diese Kacheln zwischengespeichert (also gecached) werden. Dies kann auf dem Server geschehen, der bereits alle Kacheln vorberechnen kann und bei einer Anfrage direkt eine Datei zurückschicken kann, ohne ein Bild neu berechnen zu müssen. Es erlaubt aber auch ein clientseitiges Caching, das heisst der Browser – oder im Fall von Swiss Locator QGIS – kann jede Kachel einfach wiederverwenden, ganz ohne den Server nochmals zu kontaktieren. Dadurch kann die Reaktionszeit enorm gesteigert werden und flott mit Applikationen gearbeitet werden.

Warum also noch WMS verwenden?

Auch das hat natürlich seine Vorteile. Der WMS kann optimierte Bilder ausliefern für genau eine Abfrage. Er kann Beispielsweise alle Beschriftungen optimal platzieren, so dass diese nicht am Kartenrand abgeschnitten sind, bei Kacheln mit den vielen Rändern ist das schwieriger. Ein WMS kann auch verschiedene abgefragte Layer mit Effekten kombinieren, Blending-Modi sind eine mächtige Möglichkeit, um visuell ansprechende Karten zu erzeugen. Weiter kann ein WMS auch in beliebigen Auflösungen arbeiten (DPI), was dazu führt, dass Schriften und Symbole auf jedem Display in einer angenehmen Grösse angezeigt werden, währenddem das Kartenbild selber scharf bleibt. Dasselbe gilt natürlich auch für einen PDF Export.

Ein WMS hat zudem auch die Eigenschaft, dass im Normalfall kein Caching geschieht. Bei einer dahinterliegenden Datenbank wird immer der aktuelle Datenstand ausgeliefert. Das kann auch gewünscht sein, zum Beispiel soll nicht zufälligerweise noch der AV-Datensatz von gestern ausgeliefert werden.

Dies bedingt jedoch immer, dass der Server das auch entsprechend umsetzt. Bei den von swisstopo via map.geo.admin.ch publizierten Karten ist die Schriftgrösse auch bei WMS fix ins Kartenbild integriert und kann nicht vom Server noch angepasst werden.

Im Falle von QGIS Swiss Locator geht es oft darum, Hintergrundkarten zu laden, z.B. Orthofotos oder Landeskarten zur Orientierung. Daneben natürlich oft auch auch weitere Daten, von eher statischer Natur. In diesem Szenario kommen die Vorteile von WMTS bestmöglich zum tragen. Und deshalb möchten wir der QGIS Anwendergruppe Schweiz im Namen von allen Schweizer QGIS Anwender dafür danken, diese Umsetzung ermöglicht zu haben!

Der QGIS Swiss Locator ist das schweizer Taschenmesser von QGIS. Fehlt dir ein Werkzeug, das du gerne integrieren würdest? Schreib uns einen Kommentar!

Kaggle’s “Taxi Trajectory Data from ECML/PKDD 15: Taxi Trip Time Prediction (II) Competition” is one of the most used mobility / vehicle trajectory datasets in computer science. However, in contrast to other similar datasets, Kaggle’s taxi trajectories are provided in a format that is not readily usable in MovingPandas since the spatiotemporal information is provided as:

Therefore, we need to create a DataFrame with one point + timestamp per row before we can use MovingPandas to create Trajectories and analyze them.

But first things first. Let’s download the dataset:

import datetime

import pandas as pd

import geopandas as gpd

import movingpandas as mpd

import opendatasets as od

from os.path import exists

from shapely.geometry import Point

input_file_path = 'taxi-trajectory/train.csv'

def get_porto_taxi_from_kaggle():

if not exists(input_file_path):

od.download("https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/crailtap/taxi-trajectory")

get_porto_taxi_from_kaggle()

df = pd.read_csv(input_file_path, nrows=10, usecols=['TRIP_ID', 'TAXI_ID', 'TIMESTAMP', 'MISSING_DATA', 'POLYLINE'])

df.POLYLINE = df.POLYLINE.apply(eval) # string to list

df

And now for the remodelling:

def unixtime_to_datetime(unix_time):

return datetime.datetime.fromtimestamp(unix_time)

def compute_datetime(row):

unix_time = row['TIMESTAMP']

offset = row['running_number'] * datetime.timedelta(seconds=15)

return unixtime_to_datetime(unix_time) + offset

def create_point(xy):

try:

return Point(xy)

except TypeError: # when there are nan values in the input data

return None

new_df = df.explode('POLYLINE')

new_df['geometry'] = new_df['POLYLINE'].apply(create_point)

new_df['running_number'] = new_df.groupby('TRIP_ID').cumcount()

new_df['datetime'] = new_df.apply(compute_datetime, axis=1)

new_df.drop(columns=['POLYLINE', 'TIMESTAMP', 'running_number'], inplace=True)

new_df

And that’s it. Now we can create the trajectories:

trajs = mpd.TrajectoryCollection(

gpd.GeoDataFrame(new_df, crs=4326),

traj_id_col='TRIP_ID', obj_id_col='TAXI_ID', t='datetime')

trajs.hvplot(title='Kaggle Taxi Trajectory Data', tiles='CartoLight')

That’s it. Now our MovingPandas.TrajectoryCollection is ready for further analysis.

By the way, the plot above illustrates a new feature in the recent MovingPandas 0.16 release which, among other features, introduced plots with arrow markers that show the movement direction. Other new features include a completely new custom distance, speed, and acceleration unit support. This means that, for example, instead of always getting speed in meters per second, you can now specify your desired output units, including km/h, mph, or nm/h (knots).

This post is part of a series. Read more about movement data in GIS.

The QGIS conda packages have been around for a while. One of their use cases, for example, is to allow Linux users to easily install multiple versions of QGIS.

Similarly, we’ve seen posts on using PyQGIS in Jupyter notebooks. However, I find the setup with *.bat files rather tricky.

This post presents a way to set up a conda environment with QGIS that is ready to be used in Jupyter notebooks.

The first steps are to create a new environment and install QGIS. I use mamba for the installation step because it is faster than conda but you can use conda as well:

(base) PS C:\Users\anita> conda create -n qgis python=3.9

(base) PS C:\Users\anita> conda activate qgis

(qgis) PS C:\Users\anita> mamba install -c conda-forge qgis=3.28.2

(qgis) PS C:\Users\anita> qgis

If we now try to import the qgis module in Python, we get an error:

(qgis) PS C:\Users\anita> python

Python 3.9.15 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Nov 22 2022, 08:41:22) [MSC v.1929 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import qgis

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'qgis'

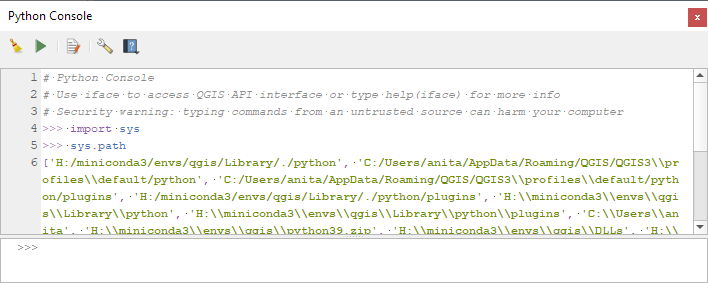

To fix this error, we need to get the paths from the Python console inside QGIS:

import sys

sys.path

['H:/miniconda3/envs/qgis/Library/./python', 'C:/Users/anita/AppData/Roaming/QGIS/QGIS3\\profiles\\default/python', ... ]

This list of paths can be configured as the defaults for our qgis environment using conda develop:

(qgis) PS C:\Users\anita> conda activate base

(base) PS C:\Users\anita> mamba install conda-build -c conda-forge

(base) PS C:\Users\anita> conda develop -n qgis [list of paths from qgis python console]

With this setup, the import should now work without errors:

(base) PS C:\Users\anita> conda activate qgis

(qgis) PS C:\Users\anita> python

Python 3.9.15 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Nov 22 2022, 08:41:22) [MSC v.1929 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> import qgis

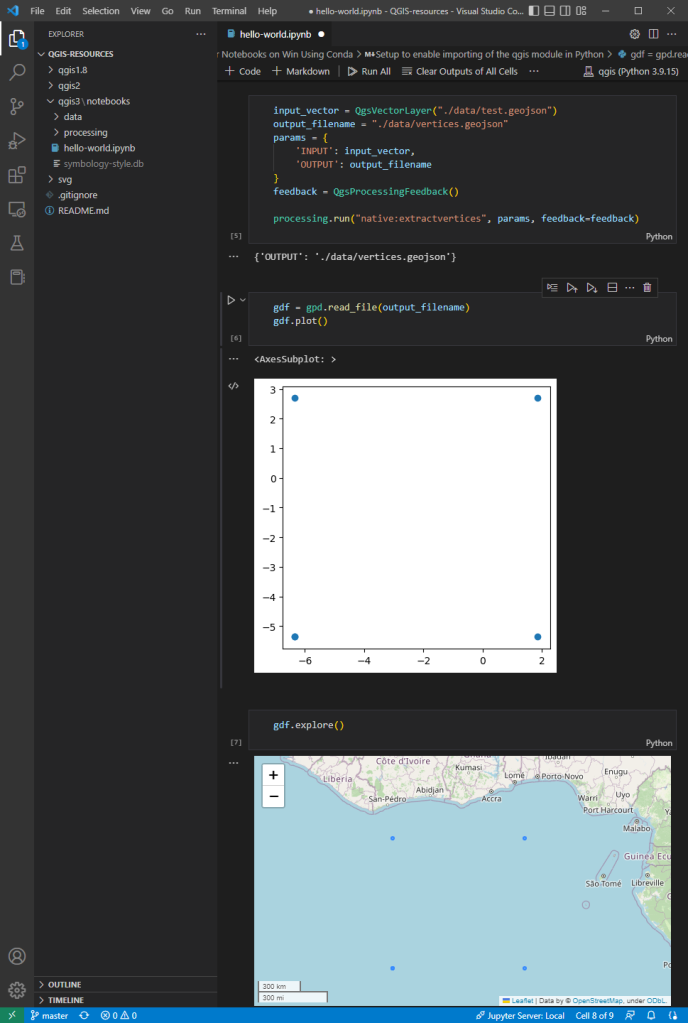

The example Jupyter notebook covers running a QGIS Processing algorithm and visualizing the results in the notebook using GeoPandas:

Head over to Github to find the full instructions: https://github.com/anitagraser/QGIS-resources/blob/master/qgis3/notebooks/hello-world.ipynb

Amongst all the processing algorithms already available in QGIS, sometimes the one thing you need is missing.

This happened not a long time ago, when we were asked to find a way to continuously visualise traffic on the Swiss motorway network (polylines) using frequently measured traffic volumes from discrete measurement stations (points) alongside the motorways. In order to keep working with the existing polylines, and be able to attribute more than one value of traffic to each feature, we chose to work with the M-values. M-values are a per-vertex attribute like X, Y or Z coordinates. They contain a measure value, which typically represents time or distance. But they can hold any numeric value.

In our example, traffic measurement values are provided on a separate point layer and should be attributed to the M-value of the nearest vertex of the motorway polylines. Of course, the motorway features should be of type LineStringM in order to hold an M-value. We then should interpolate the M-values for each feature over all vertices in order to get continuous values along the line (i.e. a value on every vertex). This last part is not yet existing as a processing algorithm in QGIS.

This article describes how to write a feature-based processing algorithm based on the example of M-value interpolation along LineStrings.

The pyqgis class QgsProcessingFeatureBasedAlgorithm is described as follows: “An abstract QgsProcessingAlgorithm base class for processing algorithms which operates “feature-by-feature”.

Feature based algorithms are algorithms which operate on individual features in isolation. These are algorithms where one feature is output for each input feature, and the output feature result for each input feature is not dependent on any other features present in the source. […]

Using QgsProcessingFeatureBasedAlgorithm as the base class for feature based algorithms allows shortcutting much of the common algorithm code for handling iterating over sources and pushing features to output sinks. It also allows the algorithm execution to be optimised in future (for instance allowing automatic multi-thread processing of the algorithm, or use of the algorithm in “chains”, avoiding the need for temporary outputs in multi-step models).”

In other words, when connecting several processing algorithms one after the other – e.g. with the graphical modeller – these feature-based processing algorithms can easily be used to fill in the missing bits.

Compared to the standard QgsProcessingAlgorithm the feature-based class implicitly iterates over each feature when executing and avoids writing wordy loops explicitly fetching and applying the algorithm to each feature.

Just like for the QgsProcessingAlgorithm (a template can be found in the Processing Toolbar > Scripts > Create New Script from Template), there is quite some boilerplate code in the QgsProcessingFeatureBasedAlgorithm. The first part is identical to any QgsProcessingAlgorithm.

After the description of the algorithm (name, group, short help, etc.), the algorithm is initialised with def initAlgorithm, defining input and output.

In our M-value example:

def initAlgorithm(self, config=None):

self.addParameter(

QgsProcessingParameterFeatureSource(

self.INPUT,

self.tr('Input layer'),

[QgsProcessing.TypeVectorAnyGeometry]

)

)

self.addParameter(

QgsProcessingParameterFeatureSink(

self.OUTPUT,

self.tr('Output layer')

)

)While in a regular processing algorithm now follows def processAlgorithm(self, parameters, context, feedback), in a feature-based algorithm we use def processFeature(self, feature, context, feedback). This implies applying the code in this block to each feature of the input layer.

! Do not use def processAlgorithm in the same script, otherwise your feature-based processing algorithm will not work ! |

This actual processing part can be copied and added almost 1:1 from any other independent python script, there is little specific syntax to make it a processing algorithm. Only the first line below really.

In our M-value example:

def processFeature(self, feature, context, feedback):

try:

geom = feature.geometry()

line = geom.constGet()

vertex_iterator = QgsVertexIterator(line)

vertex_m = []

# Iterate over all vertices of the feature and extract M-value

while vertex_iterator.hasNext():

vertex = vertex_iterator.next()

vertex_m.append(vertex.m())

# Extract length of segments between vertices

vertices_indices = range(len(vertex_m))

length_segments = [sqrt(QgsPointXY(line[i]).sqrDist(QgsPointXY(line[j])))

for i,j in itertools.combinations(vertices_indices, 2)

if (j - i) == 1]

# Get all non-zero M-value indices as an array, where interpolations

have to start

vertex_si = np.nonzero(vertex_m)[0]

m_interpolated = np.copy(vertex_m)

# Interpolate between all non-zero M-values - take segment lengths between

vertices into account

for i in range(len(vertex_si)-1):

first_nonzero = vertex_m[vertex_si[i]]

next_nonzero = vertex_m[vertex_si[i+1]]

accum_dist = itertools.accumulate(length_segments[vertex_si[i]

:vertex_si[i+1]])

sum_seg = sum(length_segments[vertex_si[i]:vertex_si[i+1]])

interp_m = [round(((dist/sum_seg)*(next_nonzero-first_nonzero)) +

first_nonzero,0) for dist in accum_dist]

m_interpolated[vertex_si[i]:vertex_si[i+1]] = interp_m

# Copy feature geometry and set interpolated M-values,

attribute new geometry to feature

geom_new = QgsLineString(geom.constGet())

for j in range(len(m_interpolated)):

geom_new.setMAt(j,m_interpolated[j])

attrs = feature.attributes()

feat_new = QgsFeature()

feat_new.setAttributes(attrs)

feat_new.setGeometry(geom_new)

except Exception:

s = traceback.format_exc()

feedback.pushInfo(s)

self.num_bad += 1

return []

return [feat_new]

In our example, we get the feature’s geometry, iterate over all its vertices (using the QgsVertexIterator) and extract the M-values as an array. This allows us to assign interpolated values where we don’t have M-values available. Such missing values are initially set to a value of 0 (zero).

We also extract the length of the segments between the vertices. By gathering the indices of the non-zero M-values of the array, we can then interpolate between all non-zero M-values, considering the length that separates the zero-value vertex from the first and the next non-zero vertex.

For the iterations over the vertices to extract the length of the segments between them as well as for the actual interpolation between all non-zero M-value vertices we use the library itertools. This library provides different iterator building blocks that come in quite handy for our use case.

Finally, we create a new geometry by copying the one which is being processed and setting the M-values to the newly interpolated ones.

And that’s all there is really!

Alternatively, the interpolation can be made using the interp function of the numpy library. Some parts where our manual method gave no values, interp.numpy seemed more capable of interpolating. It remains to be judged which version has the more realistic results. |

The last step is styling our output layer in QGIS, based on the M-values (our traffic M-values are categorised from 1 [a lot of traffic -> dark red] to 6 [no traffic -> light green]). This can be achieved by using a Single Symbol symbology with a Marker Line type “on every vertex”. As a marker type, we use a simple round point. Stroke style is “no pen” and Stroke fill is based on an expression:

with_variable(

'm_value', m(point_n($geometry, @geometry_point_num)),

CASE WHEN @m_value = 6

THEN color_rgb(140, 255, 159)

WHEN @m_value = 5

THEN color_rgb(244, 252, 0)

WHEN @m_value = 4

THEN color_rgb(252, 176, 0)

WHEN @m_value = 3

THEN color_rgb(252, 134, 0)

WHEN @m_value = 2

THEN color_rgb(252, 29, 0)

WHEN @m_value = 1

THEN color_rgb(140, 255, 159)

ELSE

color_hsla(0,100,100,0)

END

)And voilà! Wherever we have enough measurements on one line feature, we get our motorway network continuously coloured according to the measured traffic volume.

One disclaimer at the end: We get this seemingly continuous styling only because of the combination of our “complex” polylines (containing many vertices) and the zoomed-out view of the motorway network. Because really, we’re styling many points and not directly the line itself. But in our case, this is working very well.

If you’d like to make your custom processing algorithm available through the processing toolbox in your QGIS, just put your script in the folder containing the files related to your user profile:

profiles > default > processing > scripts You can directly access this folder by clicking on Settings > User Profiles > Open Active Profile Folder in the QGIS menu.

That way, it’s also available for integration in the graphical modeller.

Extract of the Graphical Modeler sequence. “Interpolate M-values neg” refers to the custom feature-based processing algorithm described above.

You can download the above-mentioned processing scripts (with numpy and without numpy) here.

Happy processing!

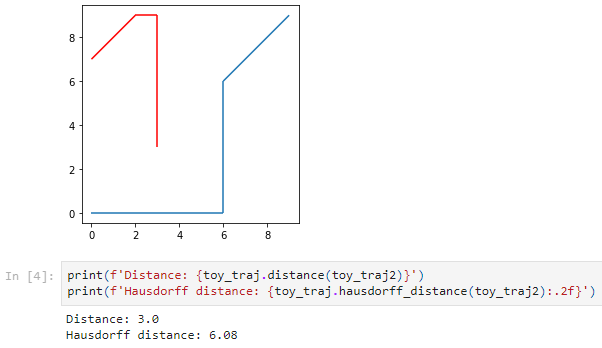

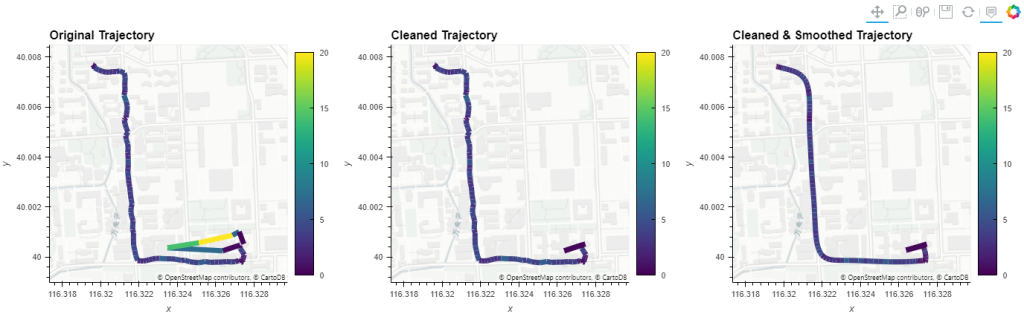

The latest v0.11 release is now available from conda-forge.

This release contains some really cool new algorithms:

As always, all tutorials are available from the movingpandas-examples repository and on MyBinder:

The new distance measures are covered in tutorial #11:

But don’t miss the great features covered by the other notebooks, such as outlier cleaning and smoothing:

If you have questions about using MovingPandas or just want to discuss new ideas, you’re welcome to join our discussion forum.

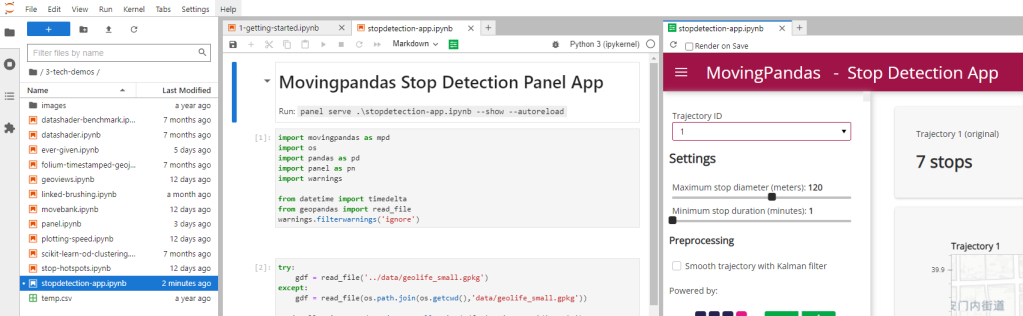

The latest v0.10 release is now available from conda-forge.

This release contains some really cool new algorithms:

If you have questions about using MovingPandas or just want to discuss new ideas, you’re welcome to join our recently opened discussion forum.

As always, all tutorials are available from the movingpandas-examples repository and on MyBinder:

Besides others examples, the movingpandas-examples repo contains the following tech demo: an interactive app built with Panel that demonstrates different MovingPandas stop detection parameters

To start the app, open the stopdetection-app.ipynb notebook and press the green Panel button in the Jupyter Lab toolbar:

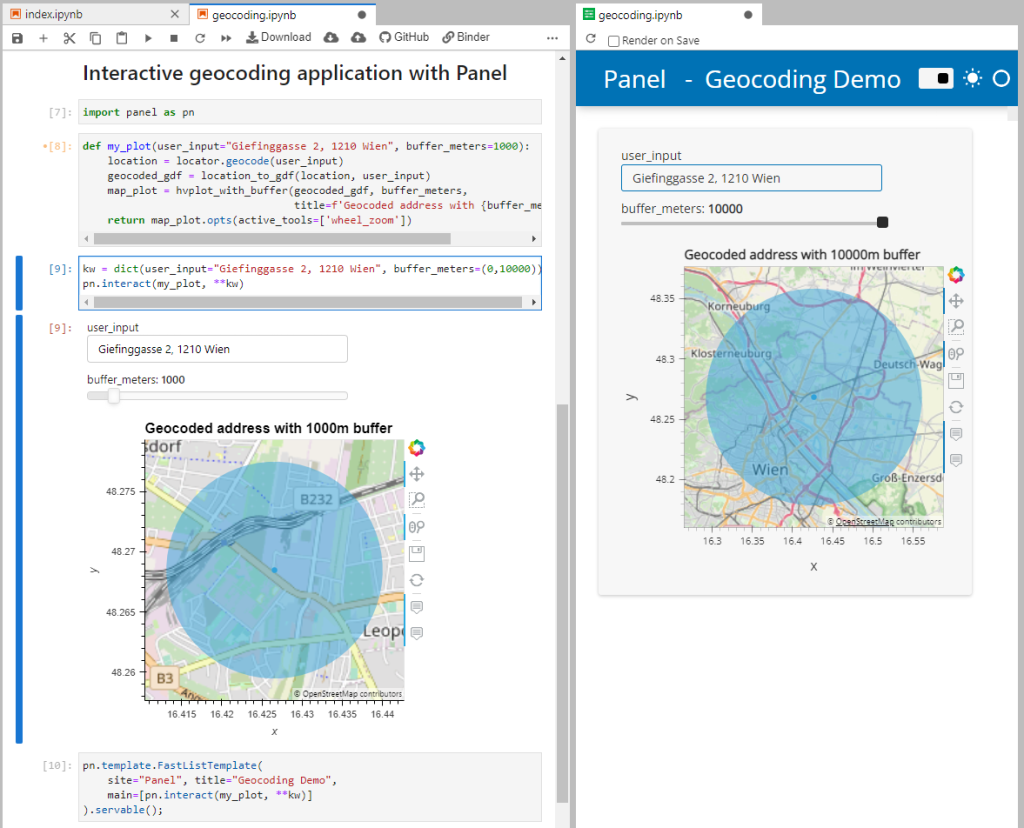

This post aims to show you how to create quick interactive apps for prototyping and data exploration using Panel.

Specifically, the following example demos how to add geocoding functionality based on Geopy and Nominatim. As such, this example brings together tools we’ve previously touched on in Super-quick interactive data & parameter exploration and Geocoding with Geopy.

Here’s a quick preview of the resulting app in action:

To create this app, I defined a single function called my_plot which takes the address and desired buffer size as input parameters. Using Panel’s interact and servable methods, I’m then turning this function into the interactive app you’ve seen above:

import panel as pn

from geopy.geocoders import Nominatim

from utils.converting import location_to_gdf

from utils.plotting import hvplot_with_buffer

locator = Nominatim(user_agent="OGD.AT-Lab")

def my_plot(user_input="Giefinggasse 2, 1210 Wien", buffer_meters=1000):

location = locator.geocode(user_input)

geocoded_gdf = location_to_gdf(location, user_input)

map_plot = hvplot_with_buffer(geocoded_gdf, buffer_meters,

title=f'Geocoded address with {buffer_meters}m buffer')

return map_plot.opts(active_tools=['wheel_zoom'])

kw = dict(user_input="Giefinggasse 2, 1210 Wien", buffer_meters=(0,10000))

pn.template.FastListTemplate(

site="Panel", title="Geocoding Demo",

main=[pn.interact(my_plot, **kw)]

).servable();

You can find the full notebook in the OGD.AT Lab repository or run this notebook directly on MyBinder:

To open the Panel preview, press the green Panel button in the Jupyter Lab toolbar:

I really enjoy building spatial data exploration apps this way, because I can start off with a Jupyter notebook and – once I’m happy with the functionality – turn it into a pretty app that provides a user-friendly exterior and hides the underlying complexity that might scare away stakeholders.

Give it a try and share your own adventures. I’d love to see what you come up with.